In a recent Encyclopedia Britannica entry on Human Geography, Johnson (2018) writes about the puzzle of structure and agency. Marxist geographers such as David Harvey have argued that people move alongside capital. According to this theoretical lens, human settlement patterns are part-and-parcel of economic geography. This view has high explanatory power, but some human geographers caution against what they see as an overly deterministic worldview. Doreen Massey, for instance, focuses on human choice and decision—which are at constant interplay with structure and are not merely their outcomes. In short, there is at least some choice in the matter of where people live.

The relevance of this theoretical discussion helps with my reading of Desbarats (1985). At the time of this writing, researchers in the United States were very interested in studying the settlement patterns of newly arrived Southeast Asian persons. Driven by Congressional mandate and also by curiosity in the academy about the life trajectories of refugees from Southeast Asia, studies such as Desbarats’ examine the where and why of migration.

There where is summarized by these maps from Desbarats (1985):

The westward population shift from 1975 to 1985 was a trend that would establish the base for further primary and secondary migration. Explaining the reasons for such migration require a variety of inquiries, including quantitative analysis done with available government data.

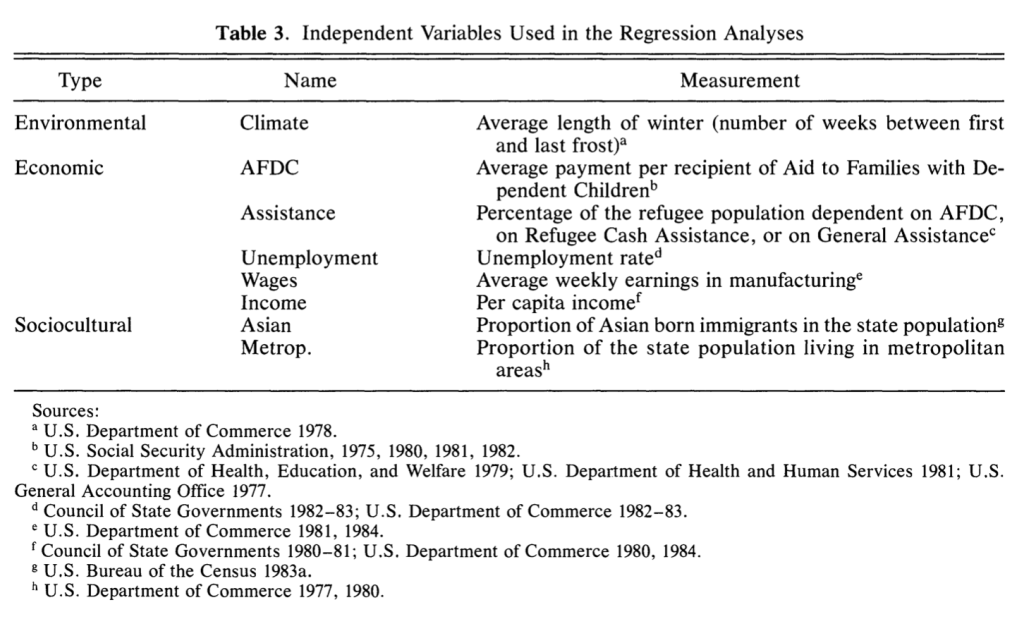

The why is summarized in the independent variables used in a regression analysis.

In a follow-up paper, Desbarats (1986), quantitative analysis shows that statistically significant factors affecting moving changed over time. For example, in 1978 “average length of winter and average per capital income” (Desbarats 1986, 58) were statistically significant factors. 1979 results show the significance of two additional factors: “AFDC benefit levels and density of Asian immigrants” (ibid, 58), while 1980 saw the loss of significance of all of these factors, with the exception of AFDC (ibid, 58). However, also in 1980, “additional explanatory factors emerged, such as manufacturing wages, metropolitan population, and the proportion of refugees on assistance, a surrogate measure for ease of eligibility” (ibid, 58).

Of course, only partial inferences can be made about migration based on this data. I’m curious about how to think about this kind of study as fundamentally different from interviews data, where we could ask each person where they moved and why. Of course, multiple methods are needed when studying a social science question such as this one, and a pragmatic philosophy—in this case, for rejecting federal dispersion policy—grounds the research. I believe we can debate this, in an interplay between Harvey and Massey-like arguments, like the one I briefly mention at the beginning of this post.

~What are your thoughts? Help me out in the comments below.~

Bibliography

Desbarats, Jacqueline. 1985. “Indochinese Resettlement in the United States.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 75 (4): 522–38.

Desbarats, Jacqueline. 1986. “Special Section: Migration and Resettlement. Policy Influences on Refugee Resettlement Patterns,” Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers 65-66: 49–63.

Johnson, Ron. 2018. “Human Geography as Locational Analysis.” In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/geography.

To what degree can social networks can sustain life when physical networks are undermined by war and immigration?

In retrospect, IMRAA’s dispersal policy seems a bit crazy—it’s a similar logic to the de-concentration of poverty targeted by urban renewal, but more precarious. Ultimately, it’s just politics, though, right? Refugee assistance is a state-funded public good. How do VOLAGs, which have clear state preferences, navigate these tensions—at the expense or benefit of refugees?

I also saw a recent report that called Vietnamese-Americans one of the most “assimilated” immigrant groups in America. Does this have anything to do with the legacy of resettlement policies?